Steer around the company’s troubled history and the visual onslaught and the Spyker is a fine car – just not the car you thought it was

It may not seem to have the same gravitas, but reviving Spyker was no less audacious than resuscitating Bugatti. True, the Dutch company had been dormant rather longer but it was still the most prestigious embodiment of a nation’s motoring history, a name that carried with it great responsibility. And don’t forget that Bugatti initially relaunched itself post-WW2 with the unloved, eight-off Type 101, long before the Romano Artioli years. Or that, while that latter era and the EB110 are revered today, commercially it was a very different story at the time. The Dutch team faced an equally monumental challenge.

Some context. The original Spyker – the Dutch spelling, Spijker, was phased out in 1903 – was to The Netherlands as Bentley was to the Brits. It had morphed out of a carriage and coachbuilder forged by blacksmith brothers Hendrik-Jan and Jacobus Spijker, and one of Spijker’s coaches is still in use by the Dutch royal family. Having embraced the horseless carriage, the company proved to be something of a pioneering powerhouse, dabbling with aerodynamics, straight-sixes and four-wheel drive. In a history that sort of mirrored Benz at that point, the 1903 front-engined straight-six 60hp was a whole raft of firsts in one – four-wheel brakes and four-wheel drive – while the 18hp shone on the 1907 Peking-Paris. Spyker’s ‘exit-WO’ moment came all too soon when, along with 127 others, Hendrik-Jan died in the SS Berlin Harwich-to-Hook of Holland ferry tragedy, prompting Jacobus also to leave.

Or maybe not all too soon, because the brothers’ departure revealed that they were better car-makers than businessmen, precipitating turbulent years of relaunches and mergers with aircraft companies before the Great War’s voracious appetite for the aircraft boosted demand, and in the process Spyker’s fortunes. Post-war, by then brandishing the natty motto Nulla Tenaci Invia Est Via (‘No road is impassable for the tenacious’) and a badge incorporating both car wheel and aero prop, more models and more records followed, including upping the Silver Ghost’s endurance record to 30,000km in a month and setting a Brooklands Double 12 best at 75mph. So did plenty more financial woes. By the 1920s Spyker was moribund, and six years later it was declared dead. It had produced an estimated 2500 (maximum) cars since 1900, the final model, the Maybach-powered C4, being the most iconic. That’s an awful lot of history for us Brits to condense into ‘Wasn’t that what Kenneth More and Kay Kendall drove in Genevieve?’ Well done us.

Unbelievably, having been reborn out of thin air at the turn of the millennium, the modern iteration(s) of Spyker has managed to squeeze as much intrigue and financial shenanigans into its own 20-year life. It started with Dutch businessman Victor Muller (initially with Maarten de Bruijn, who had the vision to buy the rights to the name in the 1990s), it bought Saab, it ran an F1 team (previously Jordan and Midland, now Racing Point via Force India) and it yo-yo’d in and out of the bankruptcy courts. Spyker is still going, in theory at least, after a 2015 bankruptcy was overturned, but there is little evidence of any car sales since.

Truth be told, annual sales never broke into three figures. The high point was just shy of 100 in 2006, the year after de Bruijn left and the start of Muller’s hokey-cokeying (in, out, in out, yes, if it needs explaining it doesn’t work). It’s a wonder they had time to build any cars, but they did and those are far more interesting than the gruesome corporate history. So it is on the motoring legacy that we will focus.

It started with de Bruijn’s Silvestris V8 – a squat Mini-Marcos-ish, Audi-powered middie that established the basic silhouette for all Spykers and appeared at the 1999 Goodwood Festival of Speed. When Muller saw it there, he joined forces with de Bruijn and the two turned the Silvestris into the Spyker C8 in time for the 2000 Birmingham Motor Show. The C8 was the template for all Spykers, whether for the 2003 Le Mans (Double 12, the only 4.0-litre; career summary – inauspicious) or for the road.

Other variants (powered by Audi’s all-aluminium 4.2-litre V8, lifted from the B7 RS4) have a range of exotic multilingual non-pattern-forming names such as Laviolette, Aileron and Preliator, but the underpinnings remain essentially the same. The aluminium spaceframe chassis is clothed in ally panels (barring the 200mph Koenigsegg-powered Preliator’s carbonfibre, though that isn’t actually proven to exist in the wild and so is a moot point), with state-of-the-art suspension and running gear. Despite some proprietary parts these were definitely not cars built down to a price. And therein lies the problem.

In fact Spyker has not built almost as many models as it has built. There was the stillborn VW Group W12-powered C12 in both La Turbie (after the hillclimb) and Zagato (after the need to cash in) versions, and myriad other cars such as the B6 Venator (probably an Artega GT), D8, D12, E8 and E12 that were bandied about yet failed to materialise. Even the cars we do know were built seemed to prove more popular with video-game developers – where Spykers were a staple – than buyers. With sales figures to which Bristol could relate (total production of maybe 350 cars), any Spyker is a rarity. But one of the LM85 commemorative editions is hen’s teeth, and the right-hooker you see here is almost unique. Very almost: one of two, in fact.

‘Laviolette’ signifies the two-piece glass roof, and it was the last incarnation of the first-gen C8 before the company started flirting with semi-automatic gearboxes, Lotus-tuned suspension and fitted Vuitton luggage. The LM85 (for Le Mans and the ‘squadron’ race number) is a road-legal version of the 2008-2010 GTR-2 racer and carries the racer’s patriotically brash Burnt Almond Orange with Gun Metal ‘S’ livery as a result. It was also promised with a Chronoswiss 24 Hour Pilot Watch with orange crocodile strap (plus the option of matching Chronoswiss in-car dials), fire retardant logo’d mats and a full hospitality weekend at Le Mans. Further scene-setting is unnecessary, I suspect.

A 2012-built car with fewer than 600 miles on the clock and not registered until 2016 would usually set alarm bells ringing, but a life split between unsold and unused is far from unusual for a Spyker. This car is as-new, and

it is wondrous in a not-exactly-wallflower way.

Some cars seem a lot more like living species than others, and this is the one I would be least surprised to see coming to life. From the beautifully symmetrical rear it is sensationally aggressive and planted, like a hand grasping into sand (though someone cruelly likened it to a ‘badly drawn Ka’). Two well-resolved exhaust stubs poke out of a mesh insert. All that jars is the circle of reflective metal beneath the numberplate (which country needs that?).

Overall, the Spyker’s proportions do not follow the modern supercar idiom apart from the obligatory scissor doors. Beyond the fractionally overlong proboscis that’s emphasised by almost zero rear overhang, the track and wheelbase are pretty square as it rides on those 19in Aeroblade propeller-style alloys (let the theming begin). Except that at 62in the rear track is a massive 7in wider than the front, so be careful at width restrictors. What abounds, apart from sheer menace, are lights and chrome, not least the roof scoop and the huge glistening ‘halo’ that sweeps from the back of the engine around the top of the screen and back again. And influences. Hints of Elise or Exige here, a bit of Maserati 3200GT there, some Veyron even, then thoughts of Peter Stevens’ MG X-Power SV conjured out of nowhere via the proliferation of slats, gills and cooling fins.

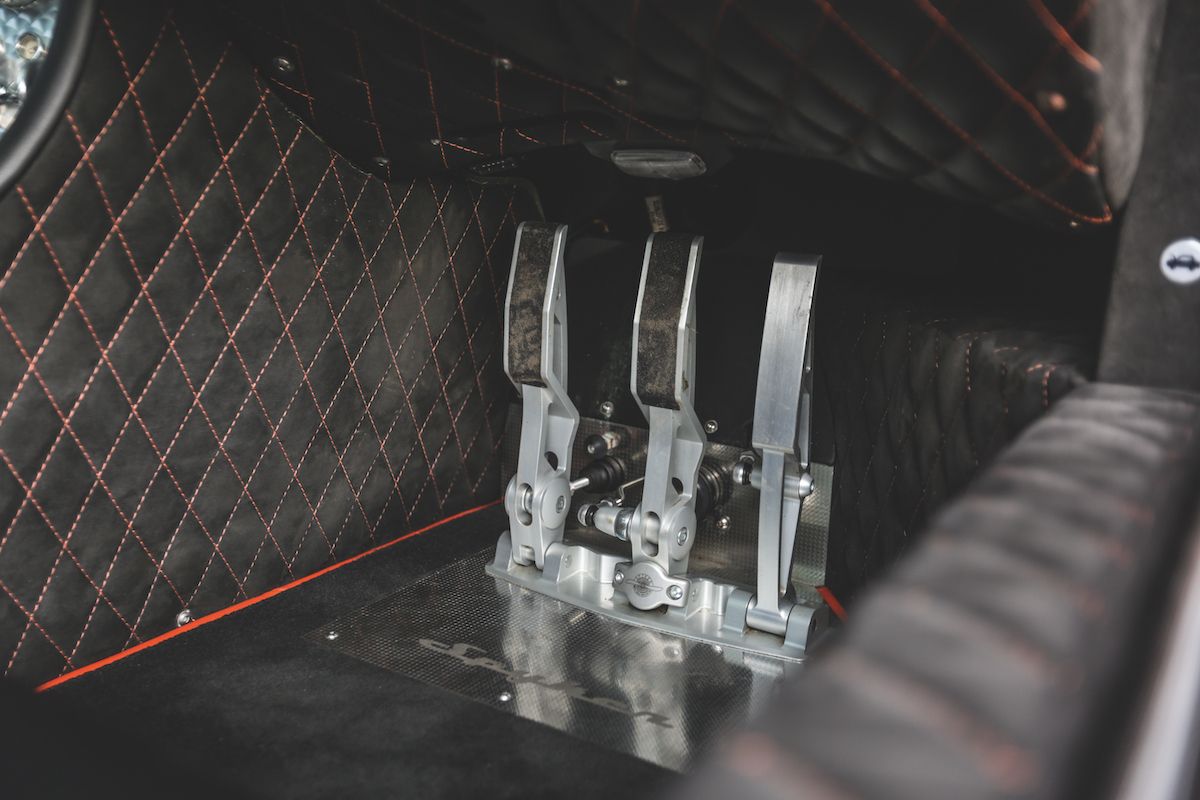

Press the button on the mirror to open the heavy scissor door and you get both the best and the worst of the Spyker. It is solid and chunky and testament that this is a proper car properly built, but then in the jamb you can see the buttons for opening bonnet or boot, each adorned with nothing sexier than an illustration of a mundane three-box saloon, possibly an Orion LX. Total buzzkill. Other than that, the cockpit is a revelation and surprisingly airy and spacious. The dash and wheel are a decent distance away, the floor-mounted pedal action the closest you will get to a full racing feeling in a road car. The driver’s seat is wonderfully comfortable and the driving position ideal.

As an experience, however, it is all a tad overpowering – not distasteful, just too much. There’s the dazzling gearlever on its massive rail, mountains of engine-turning, herds of orange stitched leather (even in the boot) and swathes of Alcantara. With logos everywhere (even on a fire extinguisher), and a mass of ivory-plus-10% dials and loads of switches, it’s like a Benelux nightclub on wheels or those guys who turn up at the Goodwood Revival dressed as The Beatles… from Sgt Pepper.

Similarly grandiloquacious is the starting procedure. If you don’t like the three-stage process with all its aero referencing, you are simply not going to like the Spyker. First, open the glovebox adorned with its Victor Muller-signed, limited-edition plaque (number 15 – of a promised 24, but who knows?), push aside the aluminium-covered owners’ manual, insert the key and turn it. Close the glovebox to hide that run-of-the-mill Audi key, then lift the red cover over the ignition toggle to make yourself feel like Pete ‘Maverick’ Mitchell and finally push the start button. The secret is not to search for logic, or even to level scorn at it as another exercise in lily-gilding, but just to slap on the Top Gun soundtrack and enjoy it.

On the road you immediately realise that this is neither a hypercar in performance nor a supercar in spirit, but more of a very rapid GT. Apart from woeful visibility (the front would be fine without the special limited-edition race team sticker covering much of the steeply raked screen, the rear-view mirror has maybe 30% of rear view) it is almost too civilised, the friendliness and comfort inside not quite echoing the OTT drama of the exterior.

That race-bred 400bhp Audi V8 really is a schizoid wonder, and so torquey. We trickled around at 20mph in sixth for maximum docility or blatted up to limit-challenging speeds in second before getting anywhere near the theoretical 7500rpm redline. But there is far more to the Spyker than just that borrowed engine. That Alcantara wheel isn’t only nice to the touch, it guides beautifully weighted and direct steering (pay-off is the supercar-sized turning circle), while that blindingly bright gearlever set-up turns out to be joyous in operation at speed. To marshall the Getrag six-speeder, the throw is barely an inch off the neutral plane at the top of the lever and a centimetre at the bottom, making it feel almost like pushing a sequential rally lever.

Similarly, the clutch is sweet to use and really engages and involves you. The super-responsive throttle is the same, and even the third pedal in that exposed aluminium set offers similar racing sensations, with only about an inch of travel to deal with all off-track circumstances via the AP Racing six-pot calipers. Don’t worry, there’s another 3-4in if you really need to stamp on them as you approach the Adelaide hairpin.

Because that is what you should do with this car: set a course for Magny Cours, travel down cosseted (great airflow, super heater), arrive fresh and give it a seeing-to on the track. It may feel like a GT, but there are heavy hints via its neutrality and lack of bodyroll, flex or unsettling weight transfer that it could be very good there. Of course that wheelbase-to-track ratio might make it unmanageable on the limit, but you never sense that it will go the full Stratos and that driving it on the limit will feel like trying to keep your legs in check your first time on ice skates. All we can say is that, given a workout on greasy A- and B-roads and with no electronic aids, the Drexler LSD is more than enough to keep the Spyker honest and you can really put the not-insignificant power down without torque steer or tail action – unless you want it.

What impresses me most, however, is the A-pillars (an Elliott obsession). They are of course thick, as they must be on a modern car, but they utilise depth rather than width. That means they may be 10-12in deep in places, but they only ever look 2in wide from the driver’s seat and your ability to see through corners

is unsullied. A gamechanger.

The sturdy, simple and comparatively lightweight LM85 feels somewhere between an Exige and an F430, but as rebirths go is Spyker really like Bugatti or more akin to Invicta and its aborted reincarnation? Or, in ambition and unchecked optimism, Tucker… or Ikenga?

None of the above, actually. Despite the inherent need to compare Spyker to other car companies (guilty, m’lud), charting its upward and downward trajectories and eventual flatlining against more familiar names is all in vain. If nothing else, Spyker was highly individual, a bit of OTT Dutch wackiness that we should all be grateful for. It’s easy for us uptight Brits to sneer at it, for sure, but Spyker should be embraced for what it is rather than what it isn’t. And what it is, is as different as it is dazzling. There are more than 30 Spyker scripts or logos on this car, but it isn’t a pastiche. These guys were proud of their heritage, their work and their car, and so they should have been.

After a while I simply stopped knowing if stuff looked terrific or tacky and, more important, I actually stopped caring. Put aside your inner D’Arcy and, as I did, you will come to love the Spyker.

Factfile – 2012 Spyker C8 Laviolette LM85

Construction Aluminium spaceframe with aluminium panels Engine Longitudinal, rear/mid-mounted 4172cc V8, DOHC per bank, 40 valves, electronic fuel injection and engine management Power 400bhp @ 6500rpm Torque 354lb ft @ 3500rpm Transmission Six-speed Getrag manual transaxle, rear-wheel drive Steering Electrically assisted rack-and-pinion Suspension Front and rear: double wishbones, coil springs, adjustable inboard Koni telescopic dampers, anti-roll bars Brakes Power-assisted vented discs, ABS Weight 1275kg Top speed 186mph 0-60mph 4.5sec

This article was originally published in Octane 204, June 2020