For years the Ferrari 250 Pinin Farina Coupé was unloved to the degree that many were butchered to make replicas of more heroic cars. Time for a change in attitude

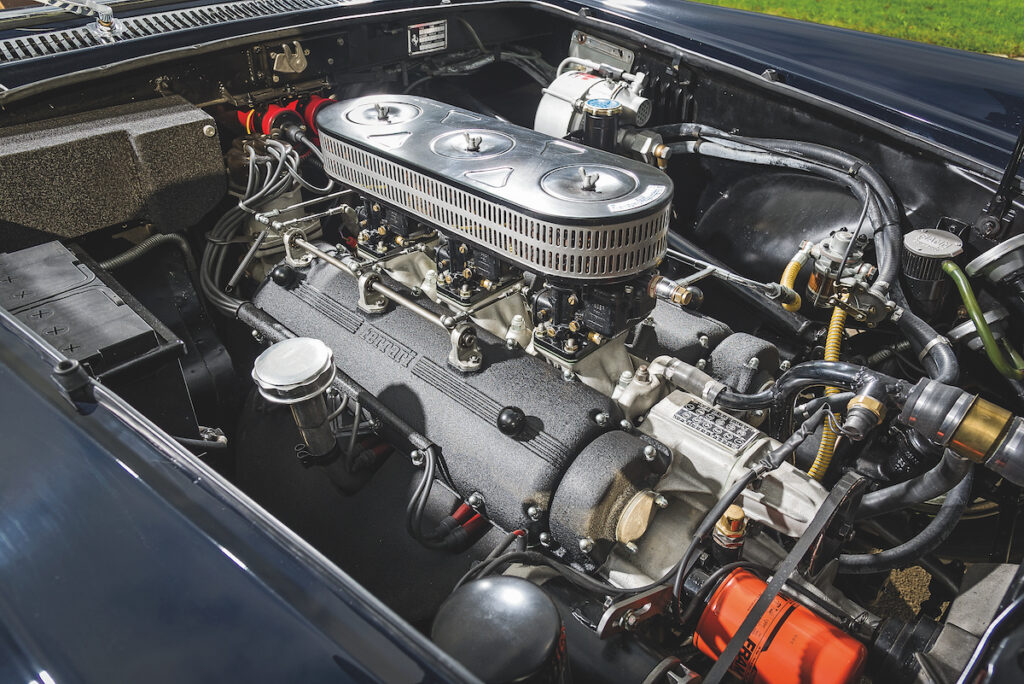

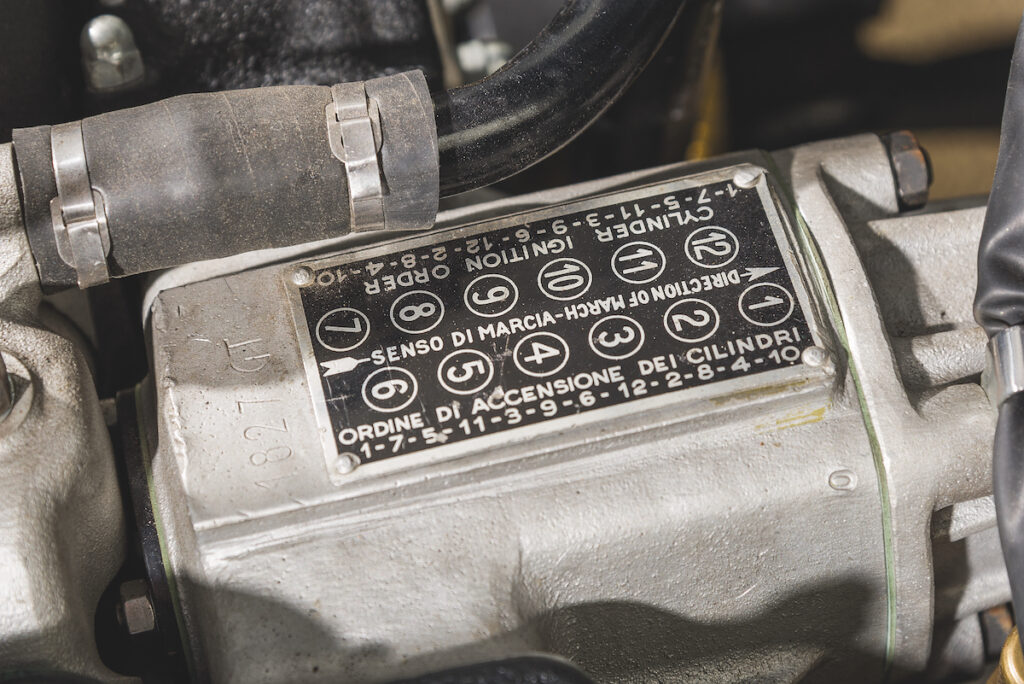

More often than not, ‘feel’ is a term reserved for when you’re trying to describe the indescribable or explain the inexplicable. In this particular instance, it’s how to get across the exhilaration you experience when starting a Ferrari 250GT (‘PF Coupé’ in marque parlance). Actually, triggering might be closer. Flick the fuel pump on, wait a moment or two for the frantic clicking to slacken, flex the throttle to prime the carbs and then pause to take a deep breath. Now twist the key half a turn and press in. There’s a whirr, followed by another, and then you’re rewarded with the sound of 12 cylinders being roused angrily from their slumber.

It doesn’t matter how many times you have heard a ‘Colombo’ V12 erupting into life, the sense of wonder is always the same. Your response is almost Pavlovian: your eyes widen, you grin broadly and you feel… goose-pimply. Really, you don’t get to enjoy this sense of

theatre with modern Ferraris. Here nothing is artificially amplified; there are no parpy flatplane-crank emissions with the 250. This is an aural tapestry of the best kind.

And then another feeling. This one doesn’t defy easy categorisation. It’s a sense of relief that this glorious machine wasn’t cut ’n’ shut, sliced ’n’ diced. Yes, this impeccably restored example might just as easily have formed the basis for a clone of one of Ferrari’s more exalted models, had its previous custodian not decided to retire and sell his inventory. That owner was one of the UK’s most prolific replicators of canonised Ferraris. You see, comparatively speaking, the ‘PF’ is a mere footnote in marque lore and has suffered historically because of it sharing a degree of parts commonality with its more exalted siblings.

But times are changing. In recent years the PF has undergone something of an image overhaul and is in demand for its actual worth rather than its value as a donor car. It’s about time too, because the importance of this model in Ferrari history cannot be overstated. While there had been previous attempts to make a production model in volume, firstly with the 250GT Europa, volume was always a relative term. As we all know by rote, Enzo Ferrari was not particularly interested in road cars. He viewed them as a means to an end, a way of funding his precious Scuderia’s racing activities, but the arrival of the 250GT Coupé at the June 1958 Milan motor show changed everything.

This wasn’t simply a race car with a few token nods to civility, it was a road car with no pretensions of being a track weapon. It was, in effect, an evolution of previous Pinin Farina design exercises produced between 1957 and ’58, but here uniformity was key. Enzo Ferrari wanted greater brand differentiation between his products and those made by his rivals, and having 101 different body styles had to this point been something of an annoyance to Il Commendatore. This new approach may have been more off-the-peg than couture, but that’s relative too. Ferrari himself described the 250GT in his memoirs, claiming it represented ‘a high fashion statement’. He wasn’t alone in thinking that.

Here was a big-boned two-seat coupé that was 65in wide and 173in long; where elegance was as much about restraint as it was about flair. Beneath the skin it borrowed from the 250GT Tour de France, not least the long-wheelbase Tipo 508 chassis. Power, meanwhile, came from a 2953cc, 240bhp unit that was rooted in Gioacchino Colombo’s classic 1.5-litre V12 race engine. Photo-journalist Bernard Cahier was particularly smitten, writing in Road & Track: ‘Ferrari’s new Gran Turismo coupé delighted everyone at its public presentation. Its distinguished and racy looks sold out the first planned series of 200 cars well in advance… The hand of Sergio Farina, Pinin Farina’s son, shows everywhere in the careful arrangements for the comfort of a driver who likes to go fast. There is plenty of room inside, and even the trunk is surprisingly large.’

The media loved the ‘PF’ even more once they got to drive it following several delays. John Bolster gushed in Autosport: ‘The main impression this car gives is of outstanding silence and smoothness. I would describe this Ferrari as a superb luxury car, combining great performance with extreme refinement to an almost unapproachable degree.’ In 1960, Road & Track borrowed the personal car belonging to Eleanor von Neumann, wife of Ferrari’s West Coast agent and race entrant John von Neumann. Its authors concluded: ‘The 250GT is as docile and meek in the low rpm range as many lesser machines and the flexibility of this engine has to be experienced to be believed.’ Rival publication Sports Car Graphic made it ‘Sports Car of the Year’ in 1960.

With a kerbweight of 1370kg (3020lb) the 250GT wasn’t exactly dainty, though it was rapid. That said, it was perhaps not as quick as Ferrari’s (ahem) ‘optimistic’ performance figures might have had you believe. The factory claimed a top speed of 150mph, but Road & Track managed ‘just’ 126mph with future Formula 1 World Champion Phil Hill at the wheel. The Motor, meanwhile, clung on for 135mph, which was still hugely impressive for a road car in 1960.

And the beautiful people flocked to land one, from captains of industry to royalty via pop minstrels and film stars; even more so after the Cabriolet variant went on sale that year, having been launched to great acclaim at the Paris motor show the previous October. Cars were constructed at Pinin Farina’s new Grugliasco facility alongside the Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider, but while the whole point of the exercise was to exert greater uniformity with body styles, this was Ferrari. Inevitably, a certain number of Speciale editions were made, the precise figure being a source of heated debate. These cars featured a degree of bespoke tailoring, the final example with its Superfast-like tail more than most.

It is widely held that 353 cars were made between 1958 and ’60, although some claim a figure of 335. During the production run, the original Tipo 128C engine was superseded by the twin-distributor 128D that, in turn, was superseded in 1960 by the ‘Outside Plug’ 128F unit, which did away with its predecessor’s siamesed inlets in favour of six separate ports. On the chassis side, four-wheel disc brakes arrived late in 1959, while an optional overdrive featured on the following year’s options list.

The unofficially named ‘second-series’ car pictured here, chassis 1827GT, left the Farina factory in April 1960 and was sold that same month to Pisa engineer Renato Buoncristiani. He paid 5,500,000 lire for the privilege, and retained the car until February 1964 when it was sold to Mrs Giovanni Fortini of Florence. Fast-forward to 1985 and the 250GT was officially exported and, by the dawn of the 2000s, it had arrived in England via the USA, in need of restoration.

However, the Ferrari only narrowly escaped being reconfigured as a faux 250GT California Spider. It arrived at Surrey’s DTR Sports Cars in November 2011 in derelict condition. ‘When we got it, the body had been removed from the chassis and the rest of the car was boxed and basically in kit form,’ DTR principal Paul de Turris recalls. ‘The engine had been stripped to the point that damage and wear were clearly visible. We had pistons made and we fully balanced the original bottom end of the engine. The cylinder heads were fully re-machined with new valves, seats, springs and so on. All ancillaries were fully rebuilt and one of the hardest parts of the restoration was locating missing items such as the pedestal fan. That part alone cost £3000! We had recently completed a 330GTS, which was a much more straightforward proposition. We made tooling in-house as needed, but were at pains to retain as many original components as humanly possible. This is a very big car so there are lots of specific bits. It has to be one of the most involved Ferraris to restore, because of its size as much as anything, but I would love to do another.’

In March 2014, the car emerged from a 2800-hour restoration resplendent in its original Blu Sera splendour. The current owner, who wishes to remain anonymous, wasted little time enjoying the finished article, often commuting in it to London from his Surrey home, and has more recently stretched its legs on Continental rallies. That it is used often comes as no great surprise from behind the wheel as it drives beautifully. All too often, cars of this ilk rarely travel much further than the end of a driveway, at least without the aid of a trailer, and they suffer as a result. Call it death by inactivity.

That said, you approach the PF Coupé with a degree of trepidation for reasons that are not, perhaps, immediately obvious. To be honest, the car’s size doesn’t intimidate as workaday family cars have grown so much in the intervening 55 years to the point that the Ferrari doesn’t appear so big by comparison with a Ford Focus or suchlike. But, whisper it, some Maranello products from this period are not that nice to drive, their real-world abilities obscured by a blizzard of hype. Yet if some prancing horse models could be described as lame, the 250GT is not among their number.

From inside the car, with its attractive blend of Connolly leather and vinyl, what strikes you first is that it is largely tinsel-free by comparison with some its period rivals. The seats are comfortable and supportive and there is plenty of aft adjustment if you’re on the tall side (the same cannot be said of, say, a 250GT SWB California Spider). Not that is in any way a 2+2, even of the comedy variety. The area behind the driver is upholstered like a seat, but it’s fit only for hand luggage.

This is a car that puts the driver at ease almost immediately. Yes, it sounds utterly glorious under load, a release of pent-up fury that renders you speechless each and every time you go near the throttle, but that is to be expected; it’s what makes a Ferrari a Ferrari. Yet by marque standards, and those of its contemporaries, what’s surprising is how tractable this car is when pottering or in traffic. It’s utterly docile at low revs, but will pull strongly from low down without hesitation and the four-speed all-synchro ’box doesn’t snatch between planes. It doesn’t like to be rushed, nor does it respond well to timidity, yet nevertheless it’s difficult to shift gears badly. By the same token, the clutch isn’t so heavy as to plait your hamstrings. The worm-and-roller steering set-up doesn’t have any dead spots and feels nicely weighted at enthusiastic speeds.

With confidence comes a more relaxed attitude. Once onto less populated B-roads, the 250GT comes into its own. A 0-60mph time of 7.1 seconds was independently verified in period, a time that seems entirely plausible, even pessimistic, but it’s more the mid-range acceleration that impresses. That short-stroke V12 just pulls and pulls and then pulls some more regardless of gear. It’s an absolute gem.

On the debit side, the PF’s ride is a little on the firm side, the hydraulic lever-action Houdaille dampers being a carry-over from earlier 250-series Ferraris. The Dunlop disc set-up works well, and there is plenty of feel through the middle pedal; history tells us that you wouldn’t want to call upon them twice in rapid succession, but the Ferrari certainly isn’t alone in that.

This is in no way a machine intended for back road bravado but it is more agile than the 250-series’ reputation for nose-heaviness might have you believe. You want to keep driving it, and ache for its continued company. As Road & Track summarised back in 1960: ‘We could ramble on for pages and pages about the Ferrari; it’s that kind of car. And it’s difficult to express our feelings of this car without resorting completely to superlatives.’

Not much has changed in the meantime, even if the species has become almost extinct. You could argue that these cars were invisible to begin with, but only if you’re a revisionist. This Ferrari matters, if only for what it represents: the jumping-off point for the marque as a manufacturer of products in volume. What’s more, it’s a wonderful car in its own right, one that makes you feel more than you can possibly say. Call it love at first hearing.

Factfile – 11960 Ferrari 250GT PF Coupé

Engine 2953cc all-alloy V12, DOHC per bank, three twin-choke Weber 40 carburettors Power 240bhp @ 7000rpm Torque 181lb ft @ 5500rpm Transmission Four-speed manual plus overdrive, rear-wheel drive Steering Worm and roller Suspension Front: wishbones, coil springs, lever-arm dampers. Rear: live axle, radius arms, coil springs, lever-arm dampers Brakes Discs Weight 1370kg Top speed: 150mph (claimed) 0-60mph: 7.1sec

This article was originally published in Octane 145, July 2015