In a previous life this Ferrari 750 Monza battled its way to victories on road and track – and it has just won the most coveted honour in the concours world

The house where Tom Peck keeps his old Ferraris is a recreation of a medieval Tuscan villa perched on a verdant hillside and overlooking some of the toniest real estate in Orange County, California. Peck’s 750 Monza, smooth as river stone and lustrous as a black sapphire, shares its stable (built of imported Italian masonry) with three other Ferraris of similar 1950s vintage. Polished to appear as exquisite jewels under the soft lights, these veteran cavallinos are enjoying a life far more pampered than Enzo Ferrari ever planned for his race cars.

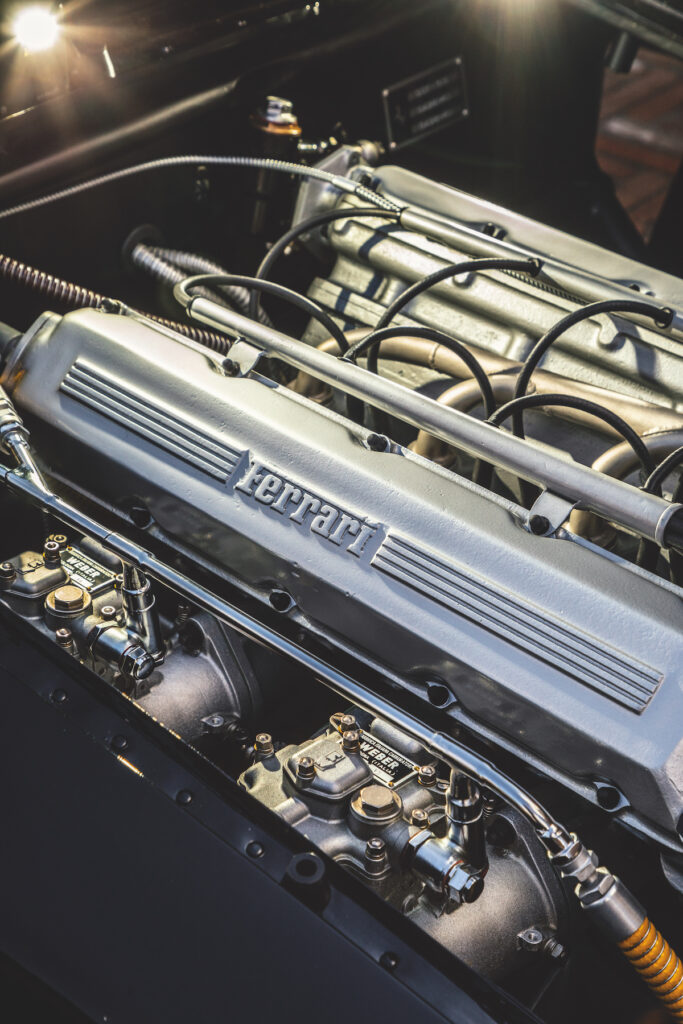

We wheel the Monza into the sunshine; it’s one of those glorious West Coast January mornings. Peck thumbs the starter and, after some clanking from the electrical components, the Aurelio Lampredi-designed twin-cam four erupts. This isn’t one of Ferrari’s sonorous little V12s greeting the morning with a lovely purr, but a big-bore war weapon that alights with a raspy, blatty, spitting, smoking, cantankerous cadence of murderous gunfire. The fearsome noise of this Italian Offy ricochets around the walls of Peck’s courtyard and spills out over the fastidiously manicured lawns of his neighbours, who will soon be swamping with complaints the community’s uniformed army of rent-a-cops. The Ferrari’s engine quits and has to be restarted several times before it will stay lit – it will be a while before it’s warm enough to maintain anything approaching an idle. But then, it wasn’t born to idle, it was born to go like hell and win.

Here’s the life Enzo had planned for this car: workers at the Maranello Scuderia slapped together chassis number 0428 MD in March 1954 in a rush to get it into the Conchiglia d’Oro (Golden Shell) race for 2.0-litre cars that June at the newly constructed Imola circuit. The 2.0-litre formula had taken over international Grand Prix racing for a short time and the Lampredi four-banger was Il Commendatore’s answer, being far simpler than Ferrari’s small V12s while offering similar power.

Just one tool in Enzo’s drawer of racing implements, this car was born to live a hard life in Ferrari’s epic battles with Maserati. It wasn’t even created as a 750 Monza originally but rather a smaller-displacement 500 Mondial (hence the MD designation in the chassis number), and the car wasn’t originally black, either, but Scuderia red. Jockeyed by factory shoe Umberto Maglioli, the 500 played its part to further Italy’s resurrection from the ashes of war by notching a win at Imola. That plus a victory

in Portugal that year would be the car’s finest hours in competition.

Only a week after Imola, the car caught fire at Monza and badly burned driver Nino Farina, who spent the next 20 days in hospital. Enzo’s boys schlepped the cooked carcass back to the factory for repairs and fresh bodywork from Carrozzeria Scaglietti. It was back at the coal-face a month later in Portugal, where factory driver José Froilán González won with it. Then, three months later at the Tourist Trophy race in Dundrod, Northern Ireland, Gonzáles went off and rolled the car. Back it went again to Scaglietti for a whole new front end, and that’s when it received the larger Type 119 3.0-litre engine, making this 500 Mondial the very first 750 Monza. However, Enzo was already done with this particular hammer and he put the car up for sale to his privateer customers.

Into our story steps Don Alfonzo Cabeza de Vaca, the 17th Marquis de Portago. ‘Fon’ to his friends, he was the lucky descendant of both Spanish royalty and an extremely rich British heiress. He was a pilot, a horseman, an Olympic bobsledder, and a crack polo player. Befitting the life of a rich dilettante, he launched his racing career not in smaller, slower cars but in a Ferrari 250 MM Vignale Spyder at the 1954 1000km enduro in Buenos Aires. After only three laps, however, the team yanked him out because nobody had bothered to instruct the 17th Marquis de Portago on how to manually shift a car (the team still finished second). Somehow Fon concluded from this experience that his next step should be to enter the most dangerous road race in the world, so he bought the 750 Monza from Ferrari in November 1954 and headed for Tuxtla Gutiérrez on the edge of the sweltering jungle in southern Mexico.

La Carrera Panamericana had begun in 1950 as a way to publicise the opening of the new Pan-American highway, but by the year of Portago’s arrival it had turned into a slaughter. Nine people died in the 1953 running, including six bystanders mowed down by Mickey Thompson in a careening Ford. Along the 1900-mile route were straights stretching to ten miles, arduous climbs to more than 10,000ft, and the occasional hay-bale heaved into the road by bored spectators. Portago barely made it out of Tuxtla before the Ferrari blew an oil line and he was forced to retire. Perhaps it was a blessing; another seven people died in 1954 after sailing over cliffs, smashing into trees, veering to avoid the ubiquitous cattle, or being hit by cars, and the Mexican Government decided to end the Carrera for good.

Portago patched up the Ferrari and raced it with some success at the Nassau Speed Week in the Bahamas before parting company with the car in late 1954 and moving on to even faster machines. Subsequently his own fatal crash in the 1957 Mille Miglia saw the end of open-road racing in Italy as well.

By then, the ageing Ferrari had slid further down the rungs of the racing ladder, running in local events in California through the latter 1950s, including the original Pebble Beach races. Finally its Lampredi 3.0-litre gave out and, because the factory was loath to supply parts for

outdated race cars, the engine was replaced with a Chevy V8 that powered it in US club events into the 1960s, where it had a few more

run-ins with immovable objects. Peck is unfazed by his car’s muddied past: ‘For many early Ferraris, that’s the only reason they’re still around, because the owners couldn’t get parts and so put in American V8s and continued to race them.’

Eventually the Ferrari ended up packed into about a hundred boxes in a warehouse in the San Francisco Bay area, where it sat for four decades until Peck heard about it from a friend in 2016 and managed to convince the ailing owner to part with it. Reunited with its original engine sometime in the early 1990s, the car was sent off to Bob Smith Coachworks, a well-known Ferrari hospital in Gainesville, Texas, where it was meticulously restored over three years while the engine was revived in the shop of Patrick Ottis in Berkeley, California.

By his own admission, Peck can’t turn a wrench, ‘so I do the research’, which has obviously been exhaustive. He spent hours looking for just the right Mobiloil Pegasus logos to put on the body. Then he had an artist tweak and resize them to match the few grainy photos of the car during its brief period in Portago’s ownership. He had stickers made, too – but was subsquently advised that decals would actually be correct, so he had them remade. Then he realised that the flying horses on the nose were backwards and should point towards the Ferrari emblem. ‘We must have $10,000 in those damn’ decals,’ he laments.

Peck bought his first Ferrari in 1979, a 308 GTS, while he was helping his dad to grow the family building products business. Work and kids always took precedence and, although new sports cars came and went, he can barely remember them now. In 2015 he bought his first vintage car, a baby blue 1954 Ferrari 500 Mondial, after selling his company and suddenly finding time and money to spare. He got hooked on the Pebble Beach Concours after winning a class award there with the 500 on his very first trip to the event.

‘I don’t go there to win, I go to try to get feedback on how to make the cars better,’ he says. Tips he’s picked up from the coterie of experts at Pebble include not painting a race car to perfection. ‘Enzo would tell his guys, “I need this car painted in a week,”’ says Peck, ‘and there was orange peel and overspray and dirt in the paint.’ Sure enough, if you lean into Peck’s black Monza you’ll notice some fog in the finish from a spray job that hasn’t been sanded until it looks like glass. Also, the number roundels and fender lettering have been painted by hand, as befits a La Carrera entry. Back then, the racers hired local sign painters in Tuxtla to adorn the cars before the start, and the brush strokes are clearly visible on Peck’s car. It certainly wowed the judges at the 2020 Cavallino Classic, and has now been declared the winner of the latest Peninsula Classics Best of the Best award.

Peck unlatches the aluminium body’s single gossamer door (it’s right-hand drive), climbs over the red leather driver’s seat and slides into the passenger seat. I try to slide gracefully behind the big wheel but it’s not easy. In the races at Nassau, according to Peck: ‘Portago would run across, jump in and go – I don’t know how he did it.’

I elect to work the closely spaced pedals in socks and am relieved that the legend on the large spun-aluminium shifter ball reveals a conventional H-pattern for the four-speed transmission, with first up and to the left. Once again, the twin-plug engine is prodded by the starter and responds with a paroxysm of guttural rage. I’ve been warned that the clutch is touchy but it has some slight give to it if you’re patient and I’m able to ease the Ferrari out of Peck’s courtyard and onto the street without stalling.

The Monza hates – really hates – going slow. The pair of side-draught 48mm dual-choke Webers will flush enough air and juice down the engine’s throat to make it surge towards 6000rpm with a hellacious fury, but they won’t abide any shyness. The car stumbles and bucks if you try to accelerate using anything much less than half-throttle, so I give it more and the Monza takes off.

The gated shifter finds its own way and, when I am firm with it and good on the double-declutch timing, the upshifts and downshifts slam home with a minimum of clash as the wind ripples our cheeks. The phone lines to the guard shack are burning as we rip back and forth through Peck’s immaculate subdivision, which for a few glorious minutes in 2021 sounded like the main drag in Tehuantepec in November 1954.

The Monza is up to temperature and all business now, its steering tight and its chassis rolling in predictable ways through the corners as the narrow tyres squish and squirm around those gorgeous Borrani wires. But the rent-a-cops have been roused and their little sport-utes with yellow flashing lights are closing in. We break for the house, because wringing out a Ferrari 750 Monza in a chi-chi Orange County enclave

is pretty much like trying to stage a bullfight at the Guggenheim; you can get away with it for only so long before somebody notices.

One can’t help but be charmed by Peck’s humble approach to his hobby. Probably the only guy in his neighbourhood who has made all the shutters on his house himself, he feels a sense of duty to get these old Ferraris out of their gilded vaults and into the world, where they can be appreciated by the next generation. He’s even talking about running the revived La Carrera Panamericana in the Ferrari, which remains a tough, bare-knuckle car-breaker, even in its modern guise.

‘Sure,’ says Peck, ‘after it’s done the show circuit, why not?’ Well, Enzo certainly never was one to let a race-car just sit around.

Factfile – 1954 Ferrari 750 Monza Prototype by Scaglietti

Engine 3000cc DOHC four-cylinder, two Weber 58DCOA3 carburettors Power 250bhp @ 6000rpm Transmission Five-speed rear-mounted transaxle Steering Worm and sector Suspension Front: double wishbones, transverse semi-elliptic leaf spring, hydraulic dampers. Rear: de Dion axle, transverse semi-elliptic leaf spring, hydraulic dampers Brakes Drums Weight 760kg Top speed 165mph

This article was originally published in Octane 214, August 2021