Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray or Ford Mustang? Very different in character, yet both of them embody the American Dream

Let’s deal with the elephant in the room first. Or rather, the photo studio. That isn’t meant as a snide dig at either the 1966 Ford Mustang GT or the 1965 Corvette Sting Ray pictured here, but rather as an acknowledgement that, to our American readers at least, the mid-60s Mustang and Corvette are not natural rivals. One was launched as a stylish shopping car, the other as a ‘halo’ sports car from a company renowned for making blue-collar sedans. As Corvette specialist and historian Tom Falconer puts it: translated into UK terms, it’s like comparing a Ford Capri with a Jaguar E-type.

Why, then, have we brought these two cars together? Because, quite simply, the Mustang and Sting Ray are the American icons of the Swinging Sixties. They are mobile works of art, cars that speak to the ordinary Kia-driver in the street just as powerfully as to the classic car geek.

But here’s the kicker. These cars are also good to drive. Twenty-eight years ago, this writer borrowed a Sting Ray convertible from the above-mentioned Tom Falconer for a long weekend, driving Britain’s Route 66 – the A66 – from one side of the country to the other. Corny idea, but the car was a revelation. And today I own a Mustang, a 1966 notchback like the one in this feature. So I make no apologies for being an evangelist for both models. Let me see if I can convert you.

Style is argument number one. It’s no coincidence that both these cars had their roots in sporty roadster concepts, or that both are still beloved by design professionals. The Mustang, in particular, seems to resonate with arty types. Former Jaguar design guru Ian Callum is a fan; British uber-architect Norman Foster keeps a 1964 Mustang at his property in Martha’s Vineyard; while former head of design at Rolls- Royce, Ian Cameron, has a 1966 notchback.

‘I’ve never driven a car that attracts as much attention from passers-by,’ says Ian, down the line from his home in Germany. ‘I prefer the notchback style, because of its proportions and understatement, and it has a great stance. I can even see something of the Mustang in the design of the Rolls Silver Shadow-based Mulliner Park Ward coupé…

‘OK, the Mustang’s build quality isn’t great, but that’s almost part of the appeal – this car is a workhorse. There’s actually very little fake ornament, other than the grilles on the rear flanks, and the interior is nicely designed. I also have a 1966 Ford Galaxie 500 two-door coupe, but the Mustang drives much better. As an all-round package, it just works.’

Ford clearly got it right with the Mustang, which debuted at the New York World’s Fair on 17 April 1964. Less than two years later, in March 1966, it had sold a million examples. But the process of getting there was a convoluted one. The first Mustang design was a radical little pointy-nosed mid-engined roadster, with a 1.9-litre V4 and independent suspension all-round. Named ‘Mustang 1’, it looked fabulous, and car guys loved it – but that was the problem. For the giant Ford corporation, it was too niche, too way out.

Several other concepts were considered and rejected – including a whole bunch codenamed Allegro, which may amuse UK readers – before one model won out. Drawn up in just three days, when presented for management approval with six rival designs ‘…it was the only one in the courtyard that seemed to be moving’, said Ford’s general manager, Lee Iacocca. The gorgeous 1966 Mustang GT pictured here is owned byretired vehicle designer John Worker (ex-GM, Ogle, Leyland and elsewhere) and is largely original, a repaint and enginerebuild aside. John’s car is a genuine GT and so, aside from bells-and-whistles such as front foglamps and dual exhausts, it has uprated suspension and a four-speed manual transmission.

The majority of V8 Mustangs were fitted with a three-speed automatic or, for six-cylinder models, a three-speed manual. The brilliance of Ford’s marketing was to create a seemingly infinite number of options, beginning with the choice of engine – 200ci (3.3-litre) straight-six or a V8, the latter initially a 260ci (4.2 litres) small-block that was superseded by the classic 289ci (4.7 litres) in late 1964 – and running a huge gamut of trim, colours and accessories. It was first available as a hardtop sedan, generally referred to as a ‘notchback’, or a convertible, but a 2+2 fastback coupe quickly joined the range. The fastback’s sportier looks often seduce buyers today but the notchback has a discreet charm of its own. It’s the purist’s choice, which is why design professionals such as Callum and Cameron prefer it.

The Corvette is in a different league altogether, though. It is one of those very rare things: a car that looks as though it went straight from concept to production without feeling the dead hands of accountants upon its bulging wings. If you were a car-mad child in 1963, when the Sting Ray was launched, it would have had a massive impact on you. Who knows, you might even have been inspired to write to General Motors and ask how to become a car designer. It certainly worked for Ed Welburn, who did just that and rose to become the head of GM design – and, significantly, the highest-ranking Afro-American to date in the global car industry. Ed is also a really nice guy, only too happy to pick up the phone when Octane calls. ‘I will absolutely never forget the first time I saw a Sting Ray in person,’ he chuckles. ‘It was a red Coupe and I was 12, going on 13. I had ridden my bicycle down to the Chevrolet dealership and was standing there, staring at it, when a passer-by jokingly asked me: “Would you like to take it for a drive?”’

Corvette generations are commonly referred to as C1, C2etc, right through to today’s C8, and the Sting Ray was the first of the C2 series, after the 1953-62 original that had debuted with a pedestrian Chevy straight-six and evolved into a fuel- injected V8 rocketship. Ed Welburn is a C2 fan, no question. ‘When I think of the C2, I immediately think of the fender shapes, very much inspired by the Italian streamliners of the 1950s. The design is so consistent all the way round – and people often forget how great the interior is, too. The C2 had an influence on every Corvette that came after it, and on other Chevrolet models, too.’

Today, Ed owns a 1957 Corvette and a 1969 Camaro – but has he ever owned a Sting Ray? ‘Don’t bring that up!’ he says in mock frustration. ‘I’ve always loved the C2 and am determined to get one, one day. And it would have to be a Coupe. I love the shape of the roofline, with or without the split window.’

Ed joined GM in 1971, when the legendary car designer Bill Mitchell was still in charge. ‘I have a great photo of me, with a huge afro, shaking hands with him when I was a young intern. We were so far apart, you would have thought there was a moat full of crocodiles between us! But he was my hero.’

As is usually the case, while Bill Mitchell is credited for ‘designing’ the Corvette, the work was actually done by a team working under his supervision. (The same thing happened with the Mustang, which was shaped by a small group of designers headed by Ford Division studio boss Joe Oros.) For the Corvette, the sketches that were developed into the finished design were produced by a very young Peter Brock back in 1959 – yes, the same Peter Brock who went on to style the Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe in 1963.

As with the Mustang, the C2 Corvette’s genesis was a complex one. The original Corvette, hobbled by its six-cylinder engine, was not a sales success and, even when Chevy brought out a V8 in 1955, it struggled to compete with Ford’s more luxurious Thunderbird. A focus on cost-cutting from top management, together with a ban on manufacturer-sponsored racing by the Automobile Manufacturers’ Association in 1957, temporarily killed off Bill Mitchell’s ambition to see a ‘hot’ Corvette go racing, but he was allowed to build a one-off concept – provided that he didn’t use the Corvette name. It was codenamed XP-87 and it was the first car to use the Stingray name – albeit as one word, rather than ‘Sting Ray’.

‘If the Corvette [race] programme had not been banned, Mitchell wouldn’t have brought the project down to Advanced Design, where us young interns were,’ explains Brock. ‘It was just fortunate timing. Mitchell had been to the Turin motor show and I think was most affected by the Alfa Disco Volante coupé – but all Italian streamliners had that same characteristic of a fairly crisp beltline with four little aerodynamic shapes over each tyre. He took photos and when he came back, he laid them out and said “This is the theme I want to work on.”

‘He turned it over to us in the studio and we sort of competed for it – as it turned out, he selected my work to continue and I became the lead on that project. Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine eventually took over and finished it up.’ Mitchell was a keen deep-sea fisherman and the Stingray name was his idea, but XP-87 was initially a roadster – ‘We couldn’t afford to build a coupe,’ says Brock. So it was serendipity that the car that became the production Sting Ray Coupe had a Ray-like spine dividing the roof and (for 1963 only) the split rear window.

‘Zora Arkus-Duntov [the Corvette’s lead engineer] went ballistic when he saw the central spine!’ recalls Brock. ‘It ended up as a pissing contest between Zora and Bill, so boss Ed Cole finally said, “OK, we’ll do it for just one year.”’

Press and customer criticism about visibility through the split rear screen gave GM the excuse it needed to swap to a one- piece unit for 1964, as shown in these pictures, and that was retained for the rest of C2 production through to 1967. The split-screen Sting Ray was a one-year model, therefore, which makes it one of the most desirable Corvettes ever made.

Performance is the second good reason to own a Mustang or Corvette. Both models were offered with a range of V8s, and even the lowest-horsepower versions would blow most European competitors into the weeds.

Today’s owners rarely drive their classics flat-out, of course, and Corvette expert Tom Falconer suggests that the base-model 327ci V8, offering a modest 250bhp, is actually the nicest to live with. ‘At normal driving speeds it has more torque than most cars of that era, and the small-block V8 has a nimbleness to its handling that the heavier big-block cannot match. That said, the lower-horsepower versions of the big-block V8 are fantastically impressive because their torque is of Tesla-like proportions.’

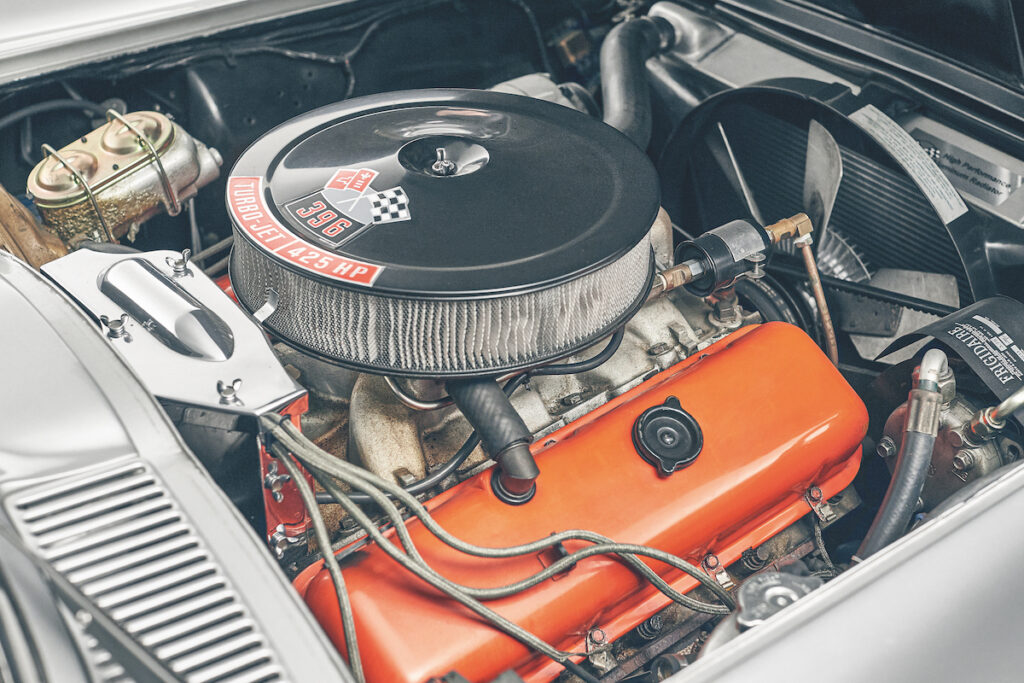

Our feature car, owned by industrial design consultant Tim FitzGerald, has the rare big-block 396ci (6.5-litre) V8 option, with a claimed 425bhp. That figure is gross, measured at the flywheel without accessories such as the alternator, and on open headers, so the real output is probably closer to 350bhp.

That’s enough for a 0-60mph time of 5.7sec, but the top speed of 140mph-plus is limited by a disquieting tendency for the car to become airborne, as Tom Falconer explains: ‘C2s are flawed by about 400lb of negative downforce – in other words, lift – at 120mph. Drive one really fast and you reach the point where you wonder whether the steering wheel is actually connected to the front wheels.’

At more sensible velocities, though, the Corvette is a delight, as I found out during 1000 miles behind the wheel of Tom’s loaner, a 1964 Convertible fitted with the 327ci engine, back in 1992. ‘It’s a real pussycat,’ I wrote. ‘The clutch and accelerator are heavy, and the gearshift has a long, clunky movement, but the steering is light and fairly accurate. You could specify high-or low-ratio steering… this one has the latter, but it’s still responsive enough to make fast driving easy.’

So far, so impressive, although I did note later that ‘…there’s a slight vagueness which dulls the car’s response as we hit the [dual carriageway’s] bends at a steady 70mph. On the straights, too, it’s best to keep a loose grip on the wheel and let it float a little, so the car finds its natural course.’

No complaints about the engine, though – and Tom’s previous comments find an echo in my notes of 28 years earlier: ‘The V8 has ludicrous amounts of torque. As long as you’ve got 2000rpm on the revcounter, you can simply floor the throttle in fourth and watch the nose rise.’

People are often surprised to hear that the Corvette has transverse leaf rear suspension, but it offers a number of advantages over coil springs (not least, overall height) and GM’s engineers got the best out of it: ‘Even on narrow, twisty lanes, the Corvette performs impressively… soaking up the bumps with ease,’ I wrote in 1992; ‘the ride is comfortable, but still taut enough to make press-on driving a pleasure.’

You could say the same about the Mustang. It’s a lighter, more nimble car running on skinnier tyres, and it feels surprisingly dainty. It’s actually more than two inches narrower than a 2020 VW Golf, and its airy glasshouse plus the ‘squariness’ of its simple three-box layout make it easy to place on the road.

My 1966 notchback has power steering; John Worker’s ’66 GT doesn’t, but the GT feels almost as light to handle on the move, and both cars have real V8 punch when you nail the throttle. The four-speed manual transmission in the GT is lighter, if not much slicker, in operation than the Corvette’s, but I like the three-speed Cruise-o-Matic in my own car, not least for its name. Cruising is what you do a lot of in a Mustang.

What’s less expected is that it’s also a remarkably rewarding car to punt along a backroad, where you can manipulate that delicate, thin-rimmed steering wheel to clip an apex with inch-perfect precision. Yes, the ride is a little bit floaty, but it’s fairly well controlled and the Mustang is far from being the wallowy, understeering monster that the ill-informed assume is typical of any American car. More often that’s due to tired suspension in neglected survivors than to any fault in design.

Front drum brakes (on my car – John’s GT has discs) might raise an eyebrow today, but I know from experience that they’re up to locking the wheels in a 60mph panic stop. Back in the day, you could specify servo-assistance for the front drums but not for the discs, curiously enough.

In terms of horsepower, the Mustang lags behind the Corvette all the way, although it compensates by being significantly lighter. Leaving aside the Shelby limited editions, the maximum output from a Mustang 289ci (4.7-litre) V8 was 270bhp gross, perhaps 210 or so in the real world. But that’s ample for a car that weighs only around 1200kg. The optional straight-six shouldn’t be ignored, either. It’s no ball of fire but it’s lighter than a V8 and has a character of its own. More importantly, the best survivor cars are often sixes because they were bought by retirees or as second cars, so tend to have led gentler lives.

Is either of these cars practical to own? Hell, yeah! The Mustang, with its Europe-friendly dimensions and superb parts availability, makes a great daily driver – in summer, at least. Rust-proofing was frequently non-existent on dry-state cars, so in a less-temperate climate they can rot faster than anything produced by Leyland or Lancia.

The Corvette benefits from a glassfibre body over a robust steel chassis. As a car for regular use rather than special outings, however, it gives ground to the Mustang, its tightly wrapped cockpit being more focused and less spacious. On a long trip, too, the Coupe can become tiring. ‘It has that early Lotus Elite feel inside over a prolonged distance, a tendency to drum, particularly if the engine has been tuned,’ says Tom Falconer.

You pay for the privilege of the Corvette’s iconic looks, too. A split-screen Sting Ray can cost up to £120,000, and the concours-winning 396 big-block (only 618 Coupes were so equipped) in our feature is insured for £110,000. Small-block 1964-67 cars are half the price at £60,000 – but that’s still a lot of money compared with Mustang values, which reflect the huge number of cars that were built.

Matthew de Leysin specialises in classic Mustangs (see midland-mustangs.co.uk) and brings a few in from the States each year; my ’66 notchback was one of them. ‘A nice V8 with good paint starts at £20,000, and a GT about £25,000,’ he says. ‘A 19641⁄2-66 notchback is still the cheapest way into Mustang ownership; if they have a bit more money, buyers tend to opt for the fastback. But with the pound weak against the dollar, it’s increasingly hard to find any classic Mustangs at a price that makes importing them viable, particularly in the dry states that are heavily shopped by the US classic car dealers.’

Truth is, whichever car you’re looking for, it can be cheaper and simpler to buy one that’s already in Europe rather than chase the romantic notion of finding a good example in the States and shipping it back. That means your slice of the American Dream may be closer to home than you think. What are you waiting for? Few dreams are as attainable or as rewarding in the long term. I know, because I’m living mine.

Factfile – 1966 Ford Mustang GT

Engine 289ci (4.7-litre) V8, pushrod OHV, Autolite 4100 4V carburettor Power 225bhp (gross) @ 4800rpm Torque 305lb ft @ 3200rpm Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive Steering Recirculating ball Suspension Front: upper wishbones, single lower control arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: semi-elliptic leaf springs, telescopic dampers Brakes Front discs, rear drums Weight 1297kg Top speed 110mph 0-60mph c9sec

Factfile – 1965 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray

Engine 396ci (6.5-litre) V8, pushrod OHV, solid lifters, Holley four barrel carburettor Power 425bhp (gross) @ 6400rpm Torque 415lb ft @ 4000rpm Transmission Four-speed close-ratio manual, rear-wheel drive Steering Recirculating ball Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: transverse leaf, halfshafts acting as upper links, lateral lower links, longitudinal control arms, telescopic dampers Brakes Ventilated discs Weight 1525kg Top speed 142mph 0-60mph 5.7sec

This article was originally published in Octane 207, September 2020